The guitar emerged from the Renaissance, for the most part, as a very small four course instrument. Although some five course guitars were known earlier, the 17th century saw the five course guitar become established as an important solo and accompaniment instrument in its own right, with virtuoso player/composers active in Italy, France, and Spain.

Baroque guitar. Folias (excerpt) by Francesco Corbetta, performed by Jakob Lindberg. BIS CD-799 (1997). Trk 1.

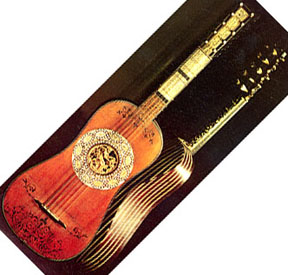

The typical baroque guitar has a recognizable guitar shape although the instrument is narrower with a more subtle “waist” than the modern guitar. Like the lute and viol family, it used gut frets tied on the fingerboard. The sound hole in the top is typically very ornate, sometimes with a gilded design, sometimes even with layers of intricate carving. Often, the back is decorated with stripes and other designs as well.

Baroque guitar. Allemande (excerpt) from Suite in D minor by Robert de Visée, performed by Nigel North. Guitar Collection. Amon Ra CD-SAR 18 (1984). Trk 12.

Baroque guitar repertoire is mostly notated in tablature like that of the lute, although there was a kind of a shorthand chordal notation called “alfabeto” that was sometimes used for song accompaniments. In terms of right-hand technique, the guitar seems commonly to have combined the “brisé” — broken — textures of finger plucking common to the lute family with strumming techniques that became so characteristic of the later guitar.

Baroque Guitar. La Coquina Francesa by Gaspar Sanz, performed by Hopkinson Smith. Gaspar Sanz: Instrucción de Música sobre la Guitarra Española. Astrée E 8576 (1996). Trk 6.